Our City, Our Space: Planning the city from an urban and human perspective

“The editions of Our City, Our Space have featured more than forty speakers and panelists from almost twenty countries, among them the global eminences on the subject Jan Gehl, Fred Kent and Gil Peñalosa; they have also brought together specialists from Havana, Cienfuegos and Matanzas.”

In an interview with journalist Katheryn Felipe, founders Gabriela García and Leysi Rubio, together with architect Gabriela Lage, talked about the challenges that both editions of this international Forum have brought to the debate, as well as the strengths and potential of the nascent Placemaking Cuba network.

Original article published in elTOQUE by KATHERYN FELIPE.

Gabriela García’s mind sketches an ideal city. She imagines it. She makes it accessible, safe, self-sustaining. She develops it with the well-being of its inhabitants in mind. She promotes the mobility of pedestrians and cyclists and builds the conditions to maintain it. In his mind, Havana, where he was born 29 years ago, has been transforming and has now learned to recycle, has promoted urban agriculture and has made its residents identify with their localities and with the processes that make it evolve.

Of course, this is just a dream that the architect, together with journalist Leysi Rubio, has been shaping for a long time. Thanks to the opportunities offered by a master’s degree at a university in the United Kingdom, the Chevening alumni strengthened their leadership and collaborative networking skills. They became interested in building a space for debate to connect those who advocate for community and sustainable development and defend public spaces.

Determined to bring about positive changes in Cuba, both obtained the support of the Chevening Alumni Programme Fund and the British Embassy in the Cuban capital to found the International Forum “Our City, Our Space”, which has been held twice. Within its framework, they also created the collaborative network Placemaking Cuba.

Foto: Cortesía del proyecto Akokán, Los Pocitos.

According to Rubio, it is “an exercise in collective reflection and creation, mutual learning and capacity building. We have the responsibility and the capacity to build a city connected to its citizens, and the formation of citizens connected to their city”.

From a perspective that may seem futuristic, García understands that “the way cities are planned affects the development of people’s lives, no matter where they come from. Urban changes can modify the reality of Cubans on a large scale and that is why, although these changes are difficult, they represent a way to move towards better and more sustainable lifestyles.

According to experts, tactical urbanism or placemaking are nothing more than urban interventions (increasingly used) that seek to recover public space and maximize its shared value, through specific, controlled actions, usually with low cost and easy implementation.

Foto: Cortesía del proyecto Akokán, Los Pocitos.

This urbanism, also called “do it yourself” and associated with the pedestrianization of streets, speaks of redistributing roads and confronting with activism the immobility that has characterized many modern cities for decades. Its most ambitious purpose lies in making humanized cities, designed by their own residents, cities in which citizens participate in decision making.

Structural changes such as giving more space to parks, sidewalks, walkways or bicycles, and less to roads or parking lots, result in a higher rate of citizen cohesion, civic identity and environmental sustainability. Described by Garcia, “it is a process that involves community members, local governments and other stakeholders collectively engaging in the development process of specific communities. It not only rehabilitates their environment, but stimulates a collective sense of identity and purpose for its inhabitants.”

The editions of [Inter]active Spaces have had the participation of more than forty speakers and panelists from almost twenty countries, among which stand out the eminences of the subject on a global scale Jan Gehl, Fred Kent and Gil Peñalosa; they have also brought together specialists from Havana, Cienfuegos and Matanzas. In fact, its main organizers intend to reach leaders from all over the island, without neglecting the gender approach.

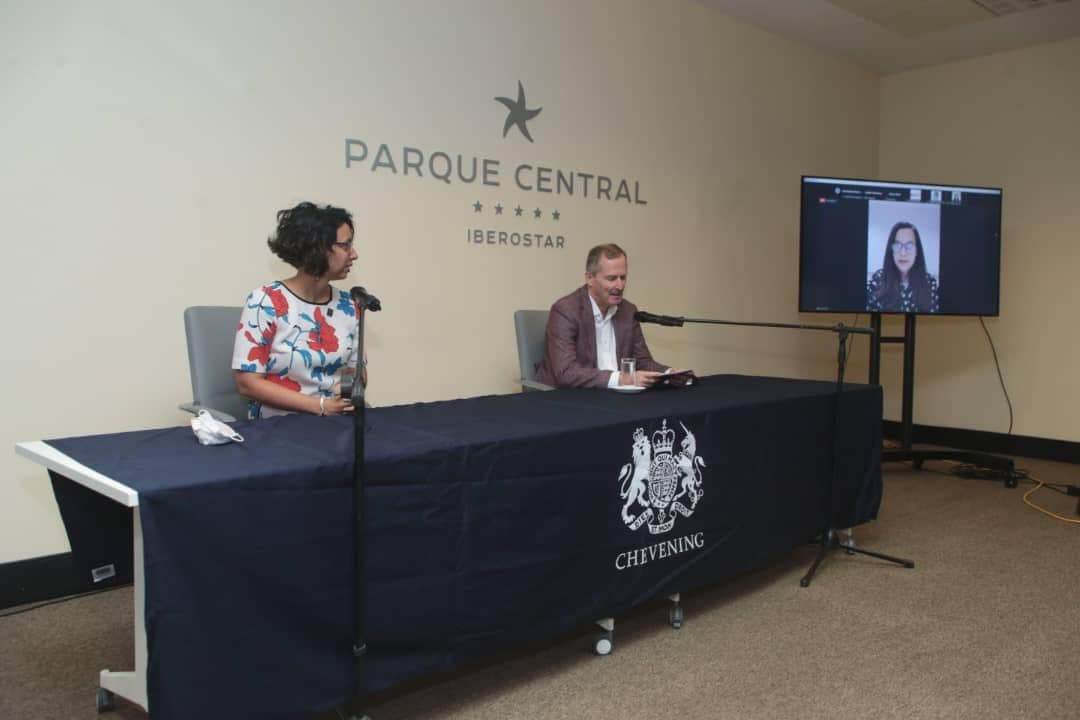

Gabriela Lage (izquierda) y Gabriela García en Espacios [Inter]activos. Foto: Cortesía de Placemaking Cuba.

An innovative idea born of young women with a strong academic background, the Forum has shown them that in a short time the essence of a neighborhood, a city, a country could be transformed. Garcia assures that it has been studied and proven that “women and men have different behaviors. This is a historical reality that makes it essential to take gender issues into account when addressing city issues. If we want them to be successful, they must, above all, be inclusive.

Although in the last two years physical distancing has made us change the way we relate to each other, the gradual return to a new normality makes it necessary that public spaces “invite people to leisure, to talk, to play, to walk, and that they are designed for all age groups and physical and mental conditions,” says the master’s degree in International Architectural Rehabilitation and Development from Oxford Brookes University.

In the words of Gabriela Lage, another architect who is among the more than thirty members currently making up Placemaking Cuba, “public space is the most democratic of cities and investing thought and resources in it benefits everyone. Because it is public, it is where we can collectively imagine how we want our cities to be and shape a new paradigm”.

Gabriela García junto al embajador británico en La Habana, Antony Stokes, en Espacios [Inter]activos. Foto: Cortesía de Placemaking Cuba.

On the one hand, says Lage, “the coronavirus has hindered the participatory processes so necessary in the ways of doing what we defend and this is a challenge that has added to many others such as the scarcity of resources and the absence of regulatory frameworks consistent with the needs of the Cuban population today”.

On the other hand, García, who worked for three years at the Office of the City Historian (OHC) and has focused his practice and research on the regeneration of urban settlements in Havana, points out that “the pandemic and post-pandemic have drawn attention to the development strategies that have characterized modernity and have made pedestrian life and the creation of spaces for communities a priority”.

According to Lage, “the context of crisis has been a wake-up call for everyone and an opportunity to rethink the way we live. In that sense, much progress has been made in changing people’s thinking, which, in my opinion, in ‘normal’ times would perhaps have taken years. The impact of a pandemic makes us put everything in perspective and we have seen significant changes in twelve months that we would not have dreamed of for years”.

URBANIZING CUBA TACTICALLY

To achieve the transformation of community spaces, García explains that a project requires participatory mechanisms from its inception to its execution. “Those who belong to a community should be considered experts because they are the ones who know it best and because it is their aspirations and discontents that we must solve. That is placemaking, the point at which professionals and institutions only support that development which, if it is born from the community and involves them at every stage, elevates the residents’ sense of belonging to their spaces.”

If there are good urban planners, architects, designers, communicators, sociologists, community activists, academics, entrepreneurs linked to this initiative, what is missing to implement what they propose? “Strengthening alliances between academia and local leaders with the authorities. For years, dozens of professionals graduate eager to transform the city and make it more resilient, inclusive, fun, dynamic. The challenge remains to turn all these ideas into concrete actions. The desire and good ideas will never be lacking,” says García.

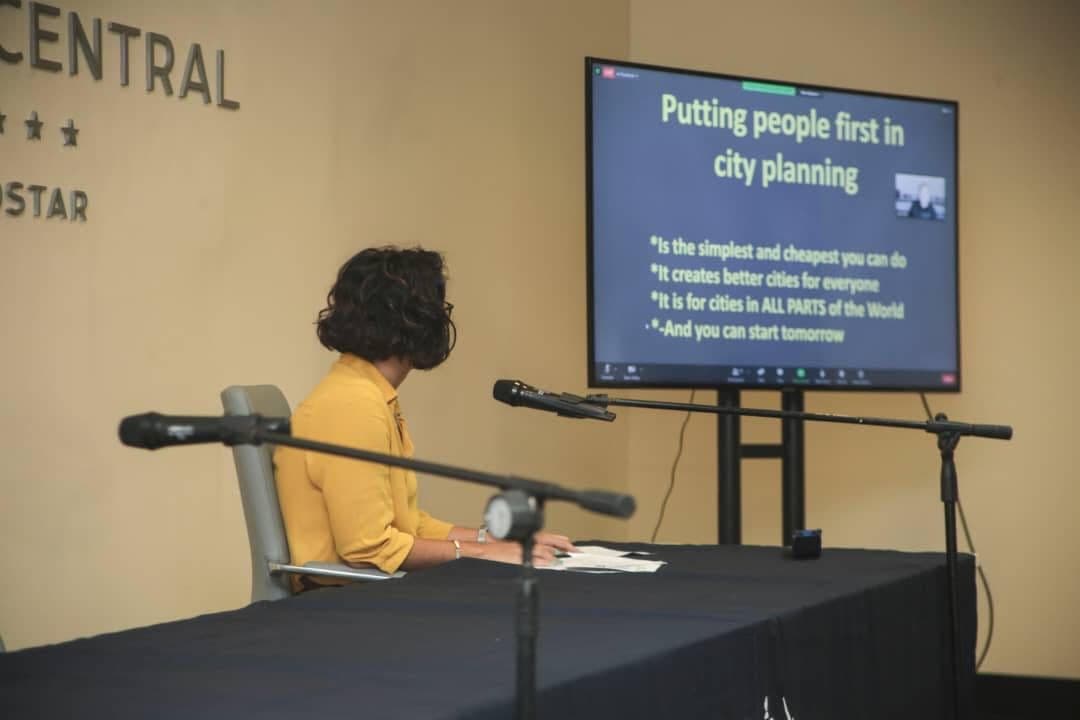

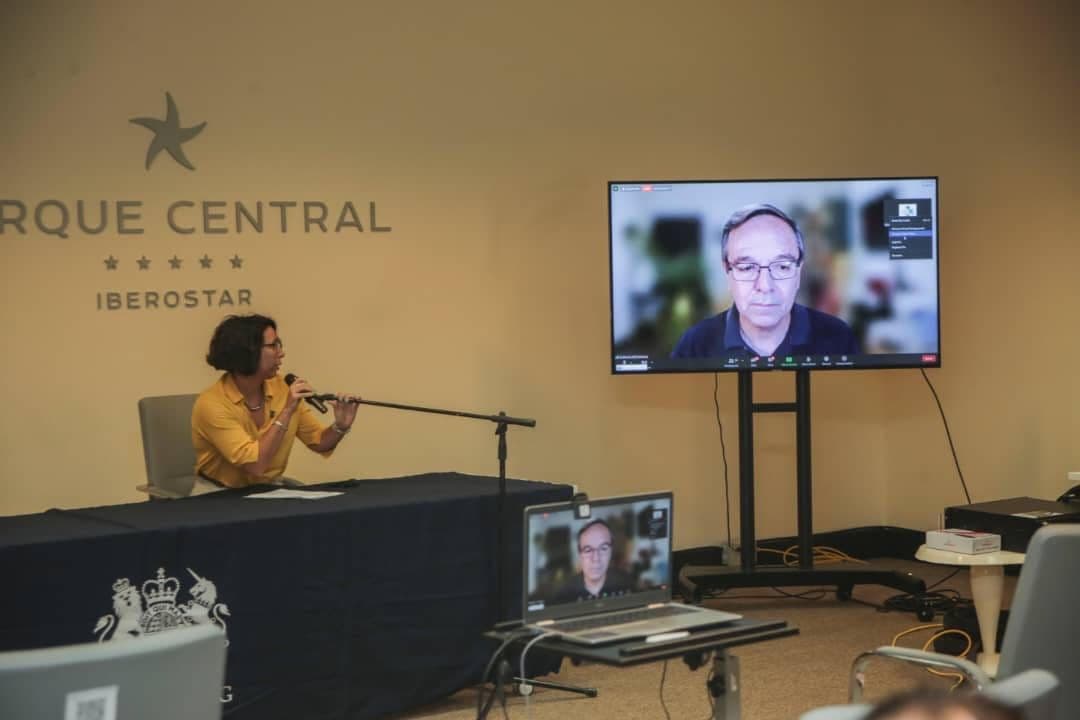

Espacios [Inter]activos. Foto: Cortesía de Placemaking Cuba.

Have the governmental strategies taken into account the debates of “Active [Inter]Spaces”, I ask him. “During the first edition the academy was the most involved, but it is a reality that the birth of local development projects favor very much what we promote in the forum since its inception and in this year’s edition we have the participation of the General Directorate of Transportation, the OHC and other institutions and NGOs that have been greatly inspired by the projects carried out by members of Placemaking Latin America. I think that with the consolidation of this network in Cuba we will be able to work together on community initiatives.

In Lage’s opinion, the main pending issue to incorporate into urban planning on the island is to look at people, “to think of them as the central axis of every project that is decided to be implemented. Ignoring their needs will lead us to failure, and that has been demonstrated”.

However, with the implementation of a Policy to Promote Territorial Development, the country is facing a much more favorable scenario to assume placemaking and consolidate influential alliances far from top-down management. For the first time in many years, notes Lage, “Cuba is beginning to see a decentralization of the economy and resources. This is very positive because what was not a priority in the country’s strategies can be addressed with more interest by local initiatives and governments. Each community can manage its resources and empower its members in a more sovereign way”.

Espacios [Inter]activos. Foto: Cortesía de Placemaking Cuba.

Data revealed by the Ministry of Economy and Planning last October state that in 2021, 423 local development projects have been implemented in Cuba, of which 314 (74.2%) are of an economic-productive nature and focus on exports, food production for people and animals, local industry, tourism and trade. Some 57 of these are socio-cultural, 21 environmental, 19 institutional and 19 research, development and innovation.

Placemaking Cuba’s first proposal was precisely a capacity building workshop with members of the Los Pocitos neighborhood, together with the Akokán project and led by Placemaking Latin America leaders. They have also had contact with other community projects such as Tercer Paraíso, Arte Corte, Ciclo Paple and Co-pincha.

Rubio explains that “they are the living experience of how to reactivate communities with a sense of responsibility and identity, with concrete high-impact projects in their localities through social and cultural management, the sustainable production of goods and services and the deployment of communicative, educational and participatory strategies for citizen empowerment”.

Espacios [Inter]activos. Foto: Cortesía de Placemaking Cuba.

The construction of infrastructures and the revitalization of those in disuse, the promotion of active mobility, the development of local economies, the promotion of recycling and food and nutritional security are key to guaranteeing access for all citizens to raw materials and their derivatives, food sources and benefits for their health, their wallets and their social and environmental surroundings.

With local development as a cornerstone, Garcia, Rubio and Lage insist on giving communities the tools to build the healthy, vibrant, sustainable and inclusive city they envision in their minds, while making creative efforts to make it happen.